This post exceeds the content limit for certain email servers, so if you’re reading this as an email and notice an abrupt cut off, simply click the headline above to read the full piece.

Several years ago, I decided to go back in time and watch hours of childhood home movies. I had just gotten divorced, quit my job, and was living alone for the first time in my life. In a desperate effort to confront my unprocessed trauma, I assumed that these painfully unfiltered, first-hand representations of my childhood might be a good place to start. I closed all the windows, crawled in bed, and nervously hit “play” as if I were preparing to watch an eight-hour slasher movie starring me as the main victim.

There were a few videos that stood out. (Don’t worry, the videos I’m about to recount didn’t depict anything particularly traumatic... I’ll get back to that storyline later).

The first was of me and a friend naked in my bedroom in 1991. We were both three years old. My dad was there, as was this little girl’s mom. The topic of genitalia came up. Apparently, my friend, let’s call her Mary, had recently learned about vaginas and penises, and how to tell them apart. She explained in broken yet adorable three-year-old English that her brother had a penis, and that she and her mom had a vagina. “What does Anya have?” her mom asked. Mary shook her head. She didn’t know. My dad chimed in, “Why don’t you take a look!”

Mary walked up to me, crouched down to look at my crotch, and very excitedly proclaimed “GINA!” Everyone laughed and cheered, but I sat still, confused and contemplative. “Mary said you have a vagina!” my dad said gleefully, trying to get me to join in on the fun.

After a few more seconds of silence, I leapt up, grabbed my vagina with both hands in an unmistakably similar manner to how men frequently grab their balls, you know, like this, and shouted “I have a penis!”

“What?” My dad asked, genuinely confused. I repeated myself clearly, still standing. “I have a penis,” I said. My dad responded again, “No, you don’t have a penis, you have a vagina.”

I sat down on the bed, shook my head pitying his ignorance and said “Naaah”.

In another video shot on my fourth birthday, my mom was filming me being gifted a tutu and a tiara. I put both on, but immediately looked unenthused. My dad suggested I go take a look in the mirror. “But I don’t like it!” I said in disgust, and pulled the tiara off my head. As I sat down to pull the tutu off my waist, I repeated myself one last time, “I, I, I really don’t like it honestly”. “Well maybe you can wear it for Halloween,” my dad suggested, with an unmistakable tone of defeat. I stood up, threw the tutu off to the side, and walked off camera victoriously. My dad shrugged, looked at my mom behind the lens, and they both chuckled.

There’s yet another video of me insisting that my mom buy me a Playmobil toy set complete with a a tractor, a trailer, a pig, a cow, and a (male) farmer. She obliged. In another, I’m playing with hot wheels cars while making loud “vroom vroom” noises.

The truth is, I never grew out of my fondness of “boy things”. I wore baggy clothes throughout my childhood, refused to take ballet, played on the boys’ hockey team, and was convinced I could teach myself how to pee standing up. I vividly remember that my favorite outfit was a pair of green, plaid, baggy cargo pants, and an oversized red t-shirt that featured the silhouette of a cowboy sitting on a fence that I got in San Antonio, TX. I wore this outfit almost every day at age eleven, and remember being bullied about it by the girls at school. Having just transferred from a very small, hippie-centric elementary school to the public middle school, I’d apparently missed the memo dictating that girls weren’t allowed to wear boy’s clothes, nor were they allowed to wear the same outfit twice in one week, let alone every day.

Thankfully, despite their initial confusion about my three-year-old penis declarations, my parents always supported my self-exploration. When I was five they got divorced, and my dad came out as gay. He made a promise to himself that he wouldn’t pass any shame onto his children, and consistently reminded my brother and me that he would love us no matter what. My parents weren’t perfect, but when it came to their open-mindedness about gender and sexuality, they were far ahead of the curve.

At twelve, I hit puberty, or puberty hit me, and got my first period on Thursday, March 8th, 2001. I remember the specific date because it also happened to be International Women’s Day. My mom, brother and I were living in Paris, France at the time, and on Women’s Day, men and boys brought home flowers as a gift for the women in their lives. As I was sitting on the toilet, yelling for my Mom to come help, my brother arrived from school with a bouquet of flowers for me. It was an unexpected coincidence, yet utterly perfect.

Despite my mother’s insistence that I didn’t need bras or razors, I demanded that she buy them for me. I got rid of most of my baggy clothes, and traded them for spaghetti strap tank tops. I kissed a boy for the first time. It felt as if I’d suddenly arrived at a destination I had never set out to reach, but that I knew was the place I was meant to end up. My relatively sudden shift from awkward, adolescent tomboy to boy-crazed, pre-teen girl hardly phased me. It didn’t feel as if I was betraying myself, or becoming someone I wasn’t meant to be. In fact, it didn’t really feel like anything at all. It had just happened.

At twenty-seven, a decade and a half later, I realized a lot more things had just happened.

I was married to a man I knew I wasn’t meant to be with, living in a city where I knew I didn’t belong, and when I looked at myself in the mirror as a married woman living in San Diego and working in marketing, I hardly recognized myself. I could see a woman standing there, she was real, flesh and bones, and she looked at least relatively attractive, put together and successful, but I didn’t know her, and perhaps more importantly, she didn’t know me.

I got divorced just seven months after getting married, left the house my husband and I had bought and renovated, and moved into an isolated cabin in Topanga Canyon at the top of a long, winding road. I committed myself to figuring out how I’d managed to wander so far off my path. I ended or took a break from a string of unhealthy, codependent relationships (including the one I had with my mother), and went to therapy three times a week.

One exercise I adopted during this time was to start asking myself why I made each decision, big or small. Why did I wash the dishes at night instead of the next morning? Was that actually what I wanted to do, or was that just what my mom or husband insisted I do in the past? Why did I wake up and go to bed at specific times? Why did I eat this particular food, but not that one? Why did I go to these sorts of events, but not those other ones? Why did I hang out with the people I hung out with? Why did I wear the clothes I was wearing?

This thought experiment turned out to be incredibly revealing as it helped me to break everything down, and start again. At the root of all of these questions was one fundamental inquiry… “Who am I?”

For starters, just like I had done at age twelve, I decided to get rid of the bulk of my clothing. Except this time I went in the opposite direction, trading dresses, skirts and fancy shoes for overalls and baggy t-shirts. I realized that somewhere along the way, I’d abandoned the tomboy aspect of my identity, and I wanted it back. I hated high-heels and makeup, so why was I wearing them? I felt far more comfortable bare-faced in Converse high-tops.

I also decided, for the first time since age twelve, to stop shaving my legs and armpits. On one hand, I was making a conscious effort to explore my own gender expression, but on the other hand, I really just wanted to know what it would feel like to have hair under my arms for the first time in my entire adult life.

This was a period of unapologetic self-exploration, and I intended to milk it for everything it was worth.

While I was busy adjusting my wardrobe and grooming routine at home, I was also busy upgrading my psychological awareness at my therapist’s office. The topic of gender and sexuality came up a lot.

Gender and sexuality were two topics I’d been interested in for a long time. I imagine that I became conscious of these interests around the same I found out my dad was gay, but it may have been even earlier than that. I remember trying to wrap my head around the nonconforming gender expression of my dad’s first long-term partner, whom he’d met when I was six. His partner referred to himself as a man, but sometimes showed up to dinner wearing a skirt and women’s shoes. I studied gender & sexuality at Sarah Lawrence College, and spent my year abroad in Amsterdam studying sexuality, gender, and religion from a cross-cultural perspective, going to gay bars, talking to sex workers in the red light district, and writing term papers about America’s exportation of religious abstinence-only education and it’s effects on the AIDS epidemic in Africa, the origin of the incest taboo as it relates to discussions of power, and the heteronormative backbone of fraternities and sororities at American universities.

After college and throughout my twenties, I abandoned these interests for a stable income, a house, a husband, and a “normal” life, only to ultimately find myself desperately unhappy and unfulfilled. After getting divorced, I was determined to reclaim these interests, both personally and intellectually, and felt excited to continue exploring them.

One afternoon while in therapy, the topic of gender came up. I had just watched the home movie clips outlined above, and I wanted to share my insights. I talked about how relieved I was to finally feel free enough to reclaim the more “masculine” aspects of my identity. Not just in my clothing or grooming choices, but also in my behavior. Throughout my twenties I had stopped standing up for myself, stopped protecting myself, didn’t set any boundaries, and I had completely neglected my own agency, autonomy, and desires, in exchange for other people’s needs and demands.

I associated my newfound sense of selfhood, and the reclamation of my independence with a reclamation of my inner masculinity, animus, or yang energy that I felt I’d long since neglected. I was resolute and impassioned to prioritize myself and my own needs over anything else.

My therapist nodded, but instead of giving me the “Yeah! You go girl!” response I was hoping for, she began to ask me a series of questions about my thoughts and feelings toward women in general.

It’s worth mentioning that at this point I had already been seeing this therapist for over a year, and, as someone who had been in therapy ten to twelve different times in my life prior to this moment, there was no doubt in my mind that this therapist was incredibly skilled. Above all else, I trusted her.

What a lot of people seem to misunderstand about therapy is that it only works when the client wants it to work. I spent years using therapy not to heal, but instead, as a means to corroborate my pre-conceived narratives and strengthen my ability to rationalize. If the therapist said something I didn’t want to hear, I would use it as a way to convince them (and myself) about why they were wrong, instead of actually listening to what they had to say, as uncomfortable and painful as that may have been. If you lie to your therapist, or try to hide from your therapist, you’re wasting your money and your time.

That said, it makes sense why we’re inclined to lie and hide. We assume that the therapeutic relationship will mirror our other relationships, where being ourselves may have proven risky, or where expressing our authenticity was restricted, dismissed, or punished. We lie and hide because that’s what we’ve had to do to survive in the past. But that’s the entire reason we’re in therapy – to deprogram those experiences and open up space for our psyches to grow into something new. The relationship we develop with a therapist is meant to mirror a new way of relating – one that’s safe and affirming. If we use the therapeutic relationship to model the unhealthy relationships we’ve had in the past by lying and hiding in fear of rejection, we’re literally paying the therapist to perpetuate our problems.

I can’t take credit for these insights. Before starting therapy after my divorce, my dad gave me some advice that had worked for him in the past. “Whatever you do,” he said, “Don’t lie. You’re incredibly smart, but the problem with your intelligence is that it allows you to convince yourself that you know better, even when you don’t. As uncomfortable as it might feel, always tell the truth.” He also suggested that I go into therapy with an intention, and that I share that intention with my therapist, which I did. I told her that I really wanted therapy to “work” this time. I told her that I wasn’t going to lie, and insisted she be straight with me. In exchange for her honesty and directness, I promised not to argue or squirm away from the discomfort, but instead to move toward it, with curiosity and open-mindedness.

So there I was, feeling self-righteous about my gender nonconformity, and being asked by my therapist how I felt about women. This seemed like an impossibly broad question to answer, so I asked her to be more specific.

“Have you generally felt comfortable with women? Let’s say, compared to men?” she asked.

That was easy to answer. I had always felt far more comfortable around men. I had an ongoing joke that I “talked about sex like a guy” and, for as long as I could remember, enjoyed hanging out and being friends with boys much more than girls. Boys were clear, direct, and I felt understood by them.

“Do you have any particularly negative memories related to girls not understanding you?” she continued.

Absolutely. That was also easy to answer. For starters, I was bullied consistently throughout elementary school and middle school. One girl was actually expelled from my elementary school for bullying me as severely as she did – cornering me in bathrooms, threatening me with violence, and telling me I was the daughter of a “filthy fucking faggot.” I had girls tell me they couldn’t be friends with me because I wasn’t pretty enough, popular enough, or interesting enough. They made fun of how big my eyes were, poked fun at my name, and told me to hold my tongue while saying “I am an apple,” so that it would sound like I was saying “I am an asshole”.

I recounted all of this to my therapist, but also explained how I didn’t think this was a particularly unique experience. Surely every girl has been a victim of girl on girl bullying. Tina Fey made a whole movie about it!

“It’s common, yes, but your case sounds particularly severe” my therapist replied, continuing her questions. “And what about negative experiences with boys? Can you think of any?”

I could think of one or two instances where a boy had bullied me, but the list was far shorter than the run-ins with girls.

“Do you feel like these events, the ones with boys and girls, affected you in different ways?”

“Yes,” I said. I explained that when the boys bullied me, it wasn’t fun per se, but that it didn’t hurt me the way the girls did. The boys seemed to be doing it “in good fun,” or even as a form of flirtation and admiration, whereas the girls really seemed to want to hurt me, as if they took pleasure in watching me suffer. I was left feeling as if I couldn’t trust girls, and that they weren’t safe to get close to. On the other hand, I still felt pretty trusting toward boys.

My therapist continued… “And what about now? Do you still feel that you can trust men?”

Unlike so many women I know, although I’d had a string of not so great relationships with men, and a couple of moderately aggressive encounters with drunk dudes at bars in college, I was never seriously assaulted, sexually abused, or raped by a man. Despite their imperfections, I liked men. I trusted them. I felt I understood them, and had compassion for them. I explained to my therapist that I assumed a lot of this sense of trust was also fostered by the relationship I had with my dad. He was an incredibly unique father figure in that he exemplified a version of masculinity that most women don’t get to experience growing up. He was strong, sensitive, trustworthy, curious, loving, courageous, open-minded, and nurturing.

“And what about your relationship with your mom?” my therapist asked without a beat, as if she had been waiting for this cue all along.

Suddenly it felt as if the outer edges of my peripheral vision were closing in, getting darker and darker around the edges and revealing something incredibly clear and conspicuous at the very center of my perception.

I didn’t even answer the question. I just started crying.

My relationship with my mom wasn’t great, to say the least. It would require far too much time to explain all of what I mean by that in this piece, but suffice to say, after getting divorced I made a very difficult decision to cut contact with her. It had become clear to me that we were extremely enmeshed, and at twenty seven I had no idea who I was, apart from her and her expectations. A lot of my time in therapy had been spent unpacking my relationship with my mom, making one excruciating discovery after the other about how the nature of that relationship had provoked a series of problems for me in my adult life, from a lack of self-worth and shoddy sense of self, to toxic and codependent relational patterns.

The reason I was crying was because I was slowly beginning to come to terms with the fact that I actually didn’t really like women. As if admitting to that fact wasn’t uncomfortable enough, it was also occurring to me that my relationship with my mom, in addition to the girls who bullied me at school, must have something to do with it. And, if all of that was true, then the very clear and conspicuous insight at the center of my perception was revealing the distressing possibility that my rejection of “womanhood” was not so much about gender, but instead, a rejection of my mother, a fear of becoming her, and a deep-seated urge to separate from her and every other woman who’d hurt me.

All of the sudden, while crying, two memories popped into my head. I grabbed a tissue, calmed myself down, and recounted them for my therapist.

The first memory was of my mom and me in a Macy’s dressing room, in 1999. I was eleven. I was screaming at her and throwing clothes she’d picked out for me on the ground. Whether I thought the clothes she picked out felt too girly, not grown up enough, or just not my style, I was infuriated by her desire to dictate my wardrobe choices and self-expression. In retrospect, I don't think she was pressuring me, but when I felt even the slightest hint of her trying to influence me to like what she liked, it made me want to scream. And I did, loudly, in public, in a Macy’s dressing room.

The second memory took place twenty years later. Right after getting divorced, but before moving to the cabin in Topanga and coming to terms with the fact that I needed to take a break from my relationship with my mom, I lived with her in Los Angeles for three very challenging months. I had met a man who was taking me on a last minute trip to some fancy event in San Francisco, and I had nothing to wear. First, my mom suggested I borrow something from her. I begrudgingly tried on a few things, but everything felt far too flashy and feminine for my tastes. I didn’t like standing out in a crowd, and these tight red dresses and loud patterns just weren’t gonna fly. We went shopping instead.

At the store, I tried on a few things, and showed her each item. Still, everything felt too feminine for me, and I told her I didn’t like any of it. “Anya,” she responded sternly, “You’re an adult woman. It’s time to stop dressing like a scared little girl hiding in the corner.” I was furious, but thankfully old enough not to throw a fit in the dressing room this time.

After recounting these memories for my therapist, so many more like them flooded back into my consciousness. My mom and I fought a lot, about everything. While the content of the fights would change, most could be boiled down to one essential struggle.

I am not you, I never want to become you, and I want to avoid anything that makes me feel associated with you.

As is the case for many women, our mothers’ are our first example of womanhood. They embody mother, woman, female, feminine and often, wife. Ideally, as was generally the case for our communal, prehistoric ancestors, girls would’ve had regular and consistent access to many different female role models. However, our society’s shift into nuclear family units has made this far less common, narrowing our available role models down to just one

I didn’t have any additional women around growing up that could model womanhood for me, except for my mom, and this left me with an extremely limited idea of what it meant to be a woman.

After delving deeper, I started to understand that I not only felt an aversion toward women in general, but also toward womanhood and femininity. The traits I’d associated with femininity – empathy, vulnerability, openness, nurturance, and receptivity, hadn’t served me well in the past. While I’d always felt naturally inclined toward these energies, my relationships had taught me how dangerous it was to embody those things. I’d been cheated on, lied to, taken advantage of, and emotionally abused and abandoned. Instead of blaming the people who had treated me poorly, or simply walking away, I turned the blame inward. I’d try even harder to prove that I was worthy of their attention and love.

I also started to understand that it wasn’t exclusively my personal experience that led me to see femininity as dangerous, risky, weak, or at the very least, subpar to masculinity. With the advent of agriculture, and the onset of Western, colonial patriarchy, feminine traits and behaviors that had been valued among our egalitarian, hunter-gatherer ancestors, became obsolete. The value of women was reduced to their status as property owned by men.

For centuries, feminine expressions of power and value were not only rendered obsolete, but also became incredibly dangerous. Women were forced to succumb to the expectations and demands of a patriarchal society, or risk neglect, violence, and even death. From the Salem Witch Trials to centuries of abuse and violence without equal protection under the law, expressing oneself as a powerful woman was no longer viable. Women had to adapt to survive, finding new ways to protect themselves and hold power in a changing, hostile world.

The truth is, we all had to adapt to survive in the context of a society that started to value ownership over reciprocity, hierarchy over community, punishment over compassion, imprisonment over rehabilitation, and scale over sustainability. The roles of both women and men changed dramatically as a result of this shift, as did their capacity to coexist in harmony and equality.

While I firmly believe that this shift represents a net-negative for both humanity and the planet (destroying ecological balance, and provoking overpopulation, widespread disease, loneliness, unhappiness, multiple forms of inequality, etc.), I’m not so sure how much progress we’ve made in recapturing the meaningful and unique value of women and womanhood.

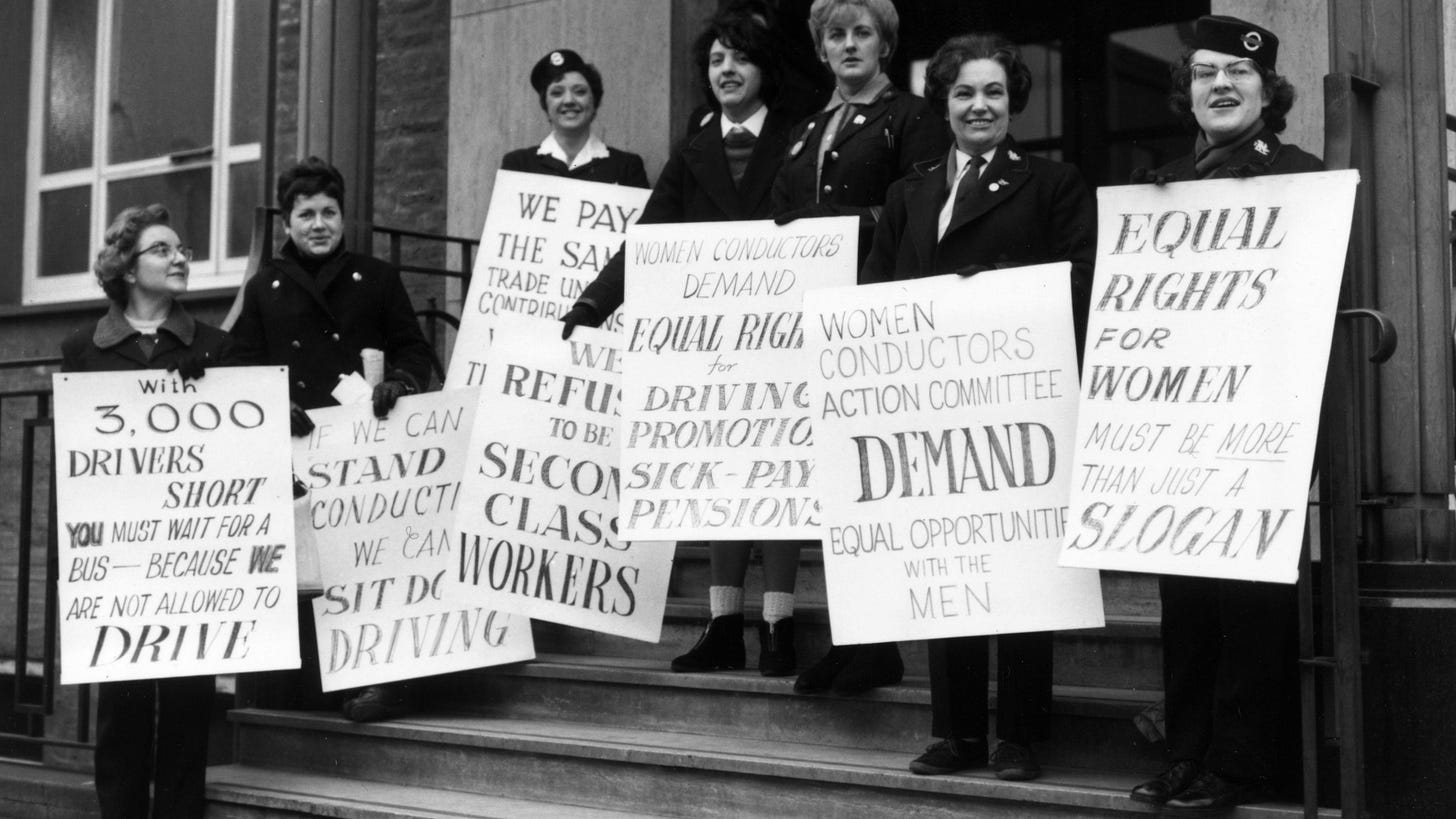

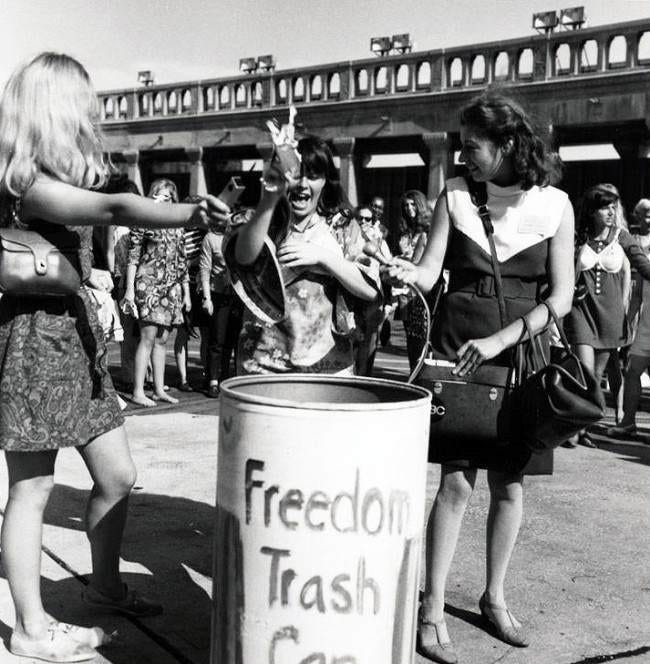

While first and second-wave feminism was revolutionary for its impact in helping women attain equal rights, it’s foundational ideology rested on the idea that in order for women to hold value in our society, they had be given equal access to domains traditionally reserved for men. They needed equal rights and equal pay to join the workforce and provide for their families, and demanded respect for their capacity to embody authority, independence, assertiveness, leadership and control. In the 1960s, women rejected feminine stereotypes by burning their bras and tossing what they called “instruments of torture” into “Freedom Trash Cans” - everything from high-heels to girdles, makeup, pink detergent, and corsets.

Let me be clear. I’m not religious, nor conservative. I don’t believe that the nuclear family, nor the institution of marriage are particularly noble ideals. Just in case I haven’t made it abundantly evident thus far, before I get into the rest of this piece, I want to make sure there’s no confusion. I don’t support the ongoing proliferation of post-agricultural, post-industrial traditional, Western, gender roles.

However.

Our initial reaction to something is rarely the solution, and in the process of correcting, we tend to overcorrect.

It’s been six years since I first came to terms with my distrust of women, and my hesitance, fear and outright rejection of “womanhood”. In many ways, my personal overcorrection was necessary in helping me find the strength and courage to extricate myself from harmful dynamics, and I firmly believe that our reactive, self-protective behavior is vital as it serves as a launchpad for change.

But reactions are not solutions.

It’s strange and slightly disturbing to recount my experiences with gender expression growing up in light of today's gender ideology movement. Had I been born twenty or thirty years later than I was, I probably would have told my parents I wanted to be a boy, especially if I knew that was an option. And I could easily understand that my parents, being the open-minded people that they are, may have ended up feeling pressured, or at the very least confused, about how to proceed appropriately.

“Some children figure out their gender really early,” claims Dr. Forcier, a gender-affirming pediatrician and professor, in a recent interview with Matt Walsh. She continues to explain that prepubescent kids are ready for hormone therapy “whenever they ask for it”.1 The Mayo Clinic claims that most children “categorize their own gender by age 3 years,”2 and lists the following behaviors as indicative of gender preference:

Certain bathroom behavior, such as a girl insisting on standing up to urinate.

An aversion to wearing the bathing suit of the child's birth sex.

A preference for underwear typically worn by the opposite sex.

A strong desire to play with toys typically assigned to the opposite sex.

Diane Ehrensaft, PhD., a gender-affirming clinical and developmental psychologist, gave a presentation to four hundred people at a recent event in Santa Cruz dedicated to continuing education about gender-affirming therapy. Here is an excerpt from her speech:

I have a colleague who is transgender. There is a video of him as a toddler–he was assigned female at birth–tearing barrettes out of then-her hair. And throwing them on the ground. And sobbing. That’s a gender message. Sometimes kids between 1 and 2, with beginning language, will say, “I BOY!” when you say “girl.” That’s an early verbal message! And sometimes there’s a tendency to say “Well, honey, no you’re a girl because little girls have vaginas, and you have a vagina so you’re a girl… Then when they get a little older [the child] says, “Did you not listen to me? I said I’m a boy with a vagina!” … Children will know [they are transgender] by the second year of life…they probably know before that but that’s pre-pre verbal.3 [emphasis mine]

I see no way of avoiding the uncomfortable reality that the child described here was me.

But the truth is, children are just as complex as gender, and the teenagers and adults they grow into are complex too.

After two years of no contact with my mom, we slowly began to reconcile, and started to build a new relationship from scratch. I spent hours sobbing, recounting the pain I’d experienced as a kid, and she listened. While she wasn’t sure if I’d ever want to have a relationship with her again after I stopped talking to her, she had put herself in therapy and learned how important it was to give her children space to live their own lives and make their own decisions.

In the past few years we’ve spoken at length (both privately and on my podcast) about the trauma my grandmother inherited from my great grandmother, that she then passed down to my mother, and that my mother passed down to me. We’ve spoken about our own complex and confusing experiences of womanhood, and shared stories of our mutual resistance to the thought of turning into our mothers. We’ve spoken about my mother’s experience of being raped in Central Park at gunpoint, and how she started dating women after that, only to eventually realize she wasn’t a lesbian, just traumatized and afraid of men. We spoke about what it was like coming to terms with my father’s homosexuality, and unpacked important details about how she raised me differently than she raised my younger brother.

We’ve spoken about what it was like for my mom to grow up with a physically abusive father, to move to New York City as a child, and to lose her older sister to breast cancer at thirty-three, when my mom was still in her late twenties. We’ve spoken about what it was like for her to watch her mom (my grandmother) become somewhat of a celebrity in the male-dominated world of publishing in the 60s and 70s, and how she always felt my grandmother’s business-savvy genes skipped a generation, and landed in me.

At thirty three, my gender expression and identity are still evolving. I still hate high heels and flashy clothes, but I’ve learned to proudly reclaim some of the other aspects of womanhood that I used to feel resistant to. I still talk about sex like a guy, but am learning to trust, confide in, and spend more time with women. I’m confident that I must have lived numerous past lives as a man, because sometimes I swear I know what it feels like to be a man, and to have a penis, but I am one hundred percent certain that I don’t actually want a penis, and that I am and always have been a woman.

I remember how controversial it was to study gender in college fifteen years ago, and to see the uncomfortable look on people’s faces when I tried to explain that gender was, by and large, socially and culturally constructed. I never denied (and still don’t) that some aspects of gender must be biologically coded (as we saw painfully illustrated in the case of David Reimer4), but what exactly rests in nature vs. nurture remains uncertain.

We’re at this pivotal point in history where there’s an opportunity to look at gender, and gender roles, in the context of not just biology and culture, but also personal and collective history. This exploration can be expansive, or contractive, and often I’m concerned it’s becoming the latter.

By listening to our three-year-old’s gender expression as literal, as opposed to an expression of complex, personal, and creative fantasy, are we opening more doors than we’re closing? By giving kids hormone blockers, are we not missing out on vital opportunities to delve deeper into their psyches in order to learn more about where their discomforts may have originated? By insisting that “trans women are women” are we inviting an ongoing dialogue to explore biological sex difference, or shrouding the mere utterance of this curiosity in shame and taboo? Does the term “cisgender” allow for enough nuance of expression, and varied evolution? How does the category of nonbinary not enforce the stereotypes of the binary? Why are we creating hundreds of new pronouns without first working to redefine the pronouns we already have, especially in light of all of the ideological and societal changes we’ve fought so hard to bring about thus far?

The root of the word “identity” comes from the Latin idem, meaning “the same”. But of course, none of us are the same as anyone else, let alone the same as we were yesterday, a week ago, or ten years ago. Hopefully, we are also not the same as who we’ll be in the future. The process of discovering ourselves rests in our capacity for inquiry, honesty, and curiosity, and is limited by our reactivity, inflexibility and our fear of “losing control”.

Gender has always been a complex recipe made from a long list of ingredients from biology to culture, personal history and trauma, to opportunity, politics, and creative expression. None of these things are mutually exclusive, and all are necessary for understanding how we develop into the complex and nuanced humans we are today.

I was recently rereading a blog I kept in college while living in Amsterdam, and came across the following quote from Judith Butler, who’s arguably the founding voice behind the idea that gender is performative as opposed to biological. Interestingly, while she’s a major proponent of the current gender ideology movement, this quote seems to be in contrast to the movement’s underlying rallying cries. "It is not possible to oppose the 'normative' forms of gender without at the same time subscribing to a certain normative view of how the gendered world ought to be."

In other words, let’s make sure we’re not creating movements and revolutions based solely on angry reactions to injustice, childish power trips and revenge fantasies that could easily end up pushing us deeper into the cages we’re trying so hard to escape from.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10875017/Pediatrician-says-prepubescent-kids-ready-HRT-ask-new-documentary.html

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/children-and-gender-identity/art-20266811

https://4thwavenow.com/2016/09/29/gender-affirmative-therapist-baby-who-hates-barrettes-trans-boy-questioning-sterilization-of-11-year-olds-same-as-denying-cancer-treatment/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Reimer

This is a fantastic piece of writing. Thank you. 🙏🏻

I recognize myself in a lot of your experiences. Always been a tomboy and more comfortable around guys. Have never really known how to talk to, or hang out with girls, (unless they were as weird and nerdy as me.) Never liked "girly" clothes or activities. Would much rather play video games. And yes, I tore the barrettes out of my hair as a kid as well. Didn't make me any less female.

I relate so much to struggling with embracing one's femininity. I'm 38 and still working on that. It's not that I don't want to be a woman, or aren't proud to be. I just don't fit the stereotype very well. A stereotype that only seems to have grown stronger in recent years. It's like there's no room for nonconformity anymore. Instead, it's more black and white than ever. And scientifically proven biology is considered offensive. Which I find so strange. Only internalized sexism would find it offensive that men's and women's bodies and minds work differently. Have evolved differently over millennia. It doesn't make one "better" than the other. Just different.

And instead of celebrating each person's right to their own (fluid) individual expression (regardless of what's between their legs), we are more and more divided into ideological groups that we're forced to comply with. (Or to borrow your brilliant expression: building more cages for ourselves.)

All of this feels oddly dystopian to me, and it's something I read and think about a lot, despite not being personally affected by it. But I'm too scared to write about it at length. So I can't thank you enough for doing so, and for bringing more complexity and nuance to this discussion. It's desperately needed. (And makes me feel less alone.) 🖤

Thank you so much for this clear, vulnerable, courageous, and insightful piece Anya. I've been studying and starting to write about gender from my own (male) point of view for the past year or so, and I've come to a lot of similar conclusions about masculinity. That is, that the advent of agriculture and industry served to greatly narrow both feminine and masculine roles, and that despite the power imbalance that came with patriarchy that has been, no doubt, in favor of men, that same patriarchal power structure served to diminish the value (and power) of both men and women. I also felt alienated from my own kind (men), and gravitated to women not only as lovers but as friends and role models.

I appreciate your point about how the nuclear family left many of us with a sole example of our own gender in the lone parent and how that exacerbated—or perhaps even led directly to—the very common feeling of "I am not you, I never want to become you, and I want to avoid anything that makes me feel associated with you"—and I do imagine that if I had had adult role male role models growing up aside from my father, that I wouldn't have felt so much the very same way, and wouldn't have alienated myself so much from him, for so very long. As so many men do.

Most of all I appreciate your expansive view of gender as one part of cultural expression, and I agree wholeheartedly that we are in a very necessary phase of explosion and redefinition of gender—and also that we are very much overcorrecting, and now in many cases further narrowing just as we are also beginning a great expansion of not-just-gender identity.

One book I've enjoyed a lot on this lately has been Grayson Perry's _The Descent of Man_. Another that comes to mind, not directly about gender at all but very much about the coming explosion of human identity in all sorts of shapes, is Bruce Sterling's classic sci-fi novella Schismatrix, published in _Schismatrix Plus_. This story often comes to mind after first reading it perhaps 30 years ago for the vivid descriptions of all sorts of varieties of people who are very much human while having also incorporated genetic and mechanistic modifications resulting in sub-species adapted for zero-gee flight in orbiting colonies, hitching rides in hard vacuum (the lobsters!), as well as various gender-bending and -multiplying varieties.

Personally, I've come to feel a lot of what Perry expresses in his book, that both masculinity and femininity are "a plurality," and "whatever you want it to be." I've been asking myself and others lately how their "femininity" or "masculinity" is different from their _individuality_, and if so, how? I do think that we carry an archetypal template that comes both from our biological sex and from a cultural inheritance of gender—and, that we can choose quite a lot of how we end up expressing gender as part of personal identity. Or at least be conscious of it. Or at least try. Because I also imagine that, of course, I show up as a man born in 1970, and that a lot of how I am will remain tied to that. I doubt that can do all that much evolving within my own lifetime—clearly, these changes are on a larger scale. I'm happy that the hard lines around gender are breaking down, and I remain a long-term optimist (certainly in part due to reading a lot of sci fi as a young person) while sharing your concern about where things stand in the near term.

A friend of mine suggested recently that the next time I, or you, or anyone is asked about their "pronouns," we respond that instead of preferring a particular gender-related pronoun, we would like to be referred to with a prefixing adjective, such as, who knows, "graceful," "stubborn," or perhaps "delicious," "majestic," "dynamic," or, some days, just "tired."