Ares & Aphrodite: The Unpredictability of Desire and Finding Creativity in Tension

Written by Anya Kaats

There was something indelible about her presence.

She was beautiful, yes, but she emanated so much more than just beauty. Her allure was a potent cocktail of love, desire, and fertility, and anyone who dared glance into her eyes was overcome with a thirst they didn’t know they had.

Women acknowledged her power in the form of jealousy and rage, and even the most dignified of men were forced to put their dignity aside, magnetized to her in ways that overpowered their judgment and reserve.

Born of sea-foam, and daughter of Chaos, she embodied the unpredictable spark that precedes all creation - emerging from a void of formlessness and perched on a scallop shell, she arrived as the personification of potential.

Her name was Aphrodite, and this is where our story begins…

By modern standards, it’s safe to assume that Aphrodite would be considered “too much.” She undoubtedly contained the “chaos” Jordan Peterson equates to the feminine in his book 12 Steps to Life: An Antidote to Chaos.

Of course, any attempt to make “order” the antidote to chaos, as Peterson proposes, assumes a false premise, because order is birthed from the fertile womb of chaos. This idea – that order, form, and structure emerge from chaos and unpredictability – is the underlying premise of “chaos theory,” for example.

The word “order” stems from the Latin ordinem, originally meaning “a row of threads in a loom,” suggesting that order is an inherently creative endeavor. “Order” and “chaos” are not opposites then, but rather, two stops on one train destined for creative expression.

In one version of her story, Aphrodite is the daughter of Chaos, the mythological realm or void state that is said to have preceded the creation of the cosmos in Greek mythology. (“Chaos” comes from the Greek khaos, meaning vast chasm and void). In another version of her story, Aphrodite sprung forth from the semen of Ouranos’ penis when it hit the sea, after he was castrated by his son Chronos. In either case, Aphrodite represented the desire for creativity, and contained that which has the potential to emerge from the fertile void.

Desire seems to emerge from nowhere, and yet, precedes the creation of everything from animals and plants to works of art and philosophical ideas. The word “desire” stems from the Latin de sidus or de sidere meaning that which comes down from the stars. Desire arrives unpredictably, turning nothingness into something-ness.

Understandably, the sheer scope of Aphrodite’s potentiality overwhelmed her fellow gods and goddesses (not to mention Jordan Peterson and the entire patriarchal world). So clearly, something had to be done.

Enter Hephaestus.

If Aphrodite represented the fecundity of desire, Hephaestus, the lame blacksmith god, represented something far more tangible and manageable. Walking with a limp and forging tools, armor, and weapons, he represented a version of creativity that could be controlled and contained.

Everyone agreed that Aphrodite needed to be controlled and contained, and so she was instructed to marry Hephaestus. (You know, the age-old “order as an antidote to chaos” strategy).

However, as we all know, most efforts to control and contain desire prove ineffective, and so in only a matter of days, Aphrodite was off seeking far more than what Hephaestus had to offer.

Aphrodite’s lover of choice? Ares, god of war.

At worst, Ares represented violence, death and unbridled destructive impulses. At best, he was also known for his courage, determination, and the act of engaging in the sacred “battles” necessary for growth, progress, and fertility.

Ares met the spark of desire that Aphrodite embodied with action and will. He represented forward motion and the capacity for manifestation. The friction and tension they sparked in one another was similar to what happens when the artist meets their muse. Aphrodite was in search of Ares’ penetrative instincts, and Ares was grateful to have something to… well, penetrate.

Aphrodite and Ares conceived three children - Deimus (god of terror), Phobus (god of fear) and Harmonia (goddess of harmony). Aphrodite not only hid her affair, but also lied to Hephaestus about the children, claiming they belonged to him.

That is, until her betrayal was exposed.

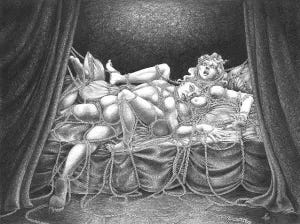

One morning, as Helios the sun god rose in the eastern sky, he caught Aphrodite and Ares together in bed. Helios informed Hephaestus of what he saw. Hephaestus was understandably humiliated and enraged, and quickly constructed a plot to get revenge.

Hephaestus forged a bronze net and hung it over the bed he shared with her. He then told her he was going on a trip, knowing she wouldn’t offer to go with him, and while he was away, waited for his revenge.

Sure enough, as expected, Aphrodite invited Ares over to spend the night, and as Helios rose the next morning, they were once again caught in bed together, this time naked and entangled in Hephaestus’ net, unable to escape.

Hephaestus returned from his trip and invited all of the gods and goddesses on Mount Olympus to witness Ares and Aphrodite’s crime against him. In front of everyone, Hephaestus demanded that Zeus condemn their crime of passion.

To Hephaestus’ great surprise, no one was empathetic. In fact, Zeus was so disgusted by Hephaestus’ vulgarity in making his private dispute with Aphrodite public, that he refused to intervene at all.

Not much changed following this debacle. Aphrodite charmed her way back into Hephaestus’ good graces (who ultimately seemed more interested in shaming Aphrodite than actually leaving her), and she returned to the sea to have her “virginity” restored. Even still, in true fashion, she then went on to conceive children with three other gods – Hermes, Poseidon, and Dionysus – all of whom also delighted her with their lustful desire.

While it may be easy to relegate Aphrodite’s archetype to that of a superficially beautiful, self-centered temptress in need of containment, as many modern patriarchal interpretations of the story do, her true nature is far more complex.

Her origin can be traced back to the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna, who represented the principles of cyclic fertilization and the transformative life/death cycles contained within creativity and renewal. The Greek philosopher Epedocles called Aphrodite the “giver of life” as she was “able to express, with heightened intensity, the ecstatic bliss of the divine love which begets and renews life”.

Ares’ reputation and history is equally nuanced. He’s frequently associated with battles, violence and aggression, but his story also contains themes related to fertility. His origin dates back to the Mesopotamian god Nergal, an agricultural god who later became associated with intense heat, scorched earth, and the destruction of crops.

Meanwhile, the Roman equivalent to Ares was Mars, a deity who was known for protecting and promoting the prosperity of the land. While many Roman gods and goddesses had sanctuaries built in their honor, the Romans considered cultivated land to be Mars’ sanctuary, thus equating his valor with “new growth.”

Additionally, the month of March and the sign of Aries (the first sign in the Zodiac) were both named after Mars/Ares, signifying the beginning of spring and the northern vernal equinox.

Correlating the fresh innocence of spring with the archetype of the warrior might seem contradictory at first, but if you’ve ever birthed a child, a new idea, or a new identity, you know that courage, determination, and heroism are all inherent to the painful labor of growth.

It seems that something must always die before substantial growth or change becomes possible. And, understandably, our fear of such a death is also what can prevent us from growing and changing in ways we know we should.

“The divine process of change manifests itself to our human understanding... as punishment, torment, death, and transfiguration.” - Carl Jung

In modern, patriarchal frameworks, both on Mount Olympus and in the twenty-first century, Ares and Aphrodite have become far more associated with the explicitly sexual and gendered components of fertility and reproduction, rather than the spiritual, “life-giving,” and cyclical aspects of their archetypes. Within this same framework, they’re also frequently associated with specifically aggressive and destructive expressions of sexuality.

To be clear, the story of Ares & Aphrodite does contain themes of the very real potential for love, desire, and sex to manifest destructively, however, when a story is stripped of its complexity, it loses its full depth, meaning, and profundity.

Ultimately, this myth, like many others, has lost much of its complexity and evolved into over-simplified archetypal themes, shaped by society’s conventional values, preferences, and paradigms.

The glyph associated with the Roman Mars (♂) has come to represent “man” or “the masculine”, and similarly, the glyph associated with Venus (the Roman equivalent to Aphrodite) has come to represent “woman” or “the feminine” (♀). As society has become increasingly repressed around sexuality, Ares and Aphrodite have been relegated to gendered bathroom placards or, thanks to the 1992 book by John Gray, used as shorthand to explain the psychological differences between men and women – “Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus.”

When interpreting mythological stories, it’s important to understand the context in which the stories were originally told. Stories that came from prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies, for example, are going to contain perspectives and values that differ greatly from stories that came out of the more modern civilizations of Greece and Rome. While many of the Greek and Roman gods evolved from earlier “less civilized” gods, their modern stories and interpretations undoubtedly evolved alongside the creation of civilized society, absorbing the values and structures necessary for the proliferation of this type of world; a world that we still live in.

The story of Ares and Aphrodite, and the evolution of their archetypal nature throughout time, point to essential and seemingly eternal conflicts that frequently arise in the realm of sex and relationships.

There is the initial conflict between Aphrodite’s “true” nature, it’s ineffability, and the attempt to contain and control it. This conflict is what gives way to her arranged marriage to Hephaestus, which then in turn generates yet another conflict in the form of Aphrodite’s affair with Ares, ultimately leading to the affair coming to light, and Hephaestus’ plot for revenge.

“Love is a battlefield,” amiright? (Insert emoji of Ares smirking).

But seriously, let’s talk about conflict.

If I were to ask you to tell me how you think modern culture approaches conflict, you might find it to be a difficult question to answer. On the one hand, conflict seems to be ubiquitous - it’s in the news, in our relationships, and in our workplaces. For those in Ukraine, conflict is quite literally what’s responsible for the loss of life and destruction they’re experiencing at this very moment.

On the other hand, our culture also seems to be incredibly resistant to conflict. We demand “safe spaces,” label common disagreements and misunderstandings “microaggressions,” and respond to minor offenses with mass campaigns to cancel people out of their very existence. Conflict has become so demonized that it’s now frequently conflated with abuse, as Sarah Shulman explains in her 2016 book Conflict is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair.

It seems we want to avoid conflict at all costs, and yet, it’s everywhere. This, of course, is a well-known symptom of what can happen when humans seek to repress, punish, or deny any intrinsic aspect of human nature. Efforts to repress natural human behavior are never successful. They simply push the behavior into unexamined and unconscious corners of the psyche, leaving it at risk of being expressed in uncontrollable, unintentional, and harmful ways.

This has been well-proven in regard to sexuality, for example. Sexual repression doesn’t eliminate sex or sexual desire, but instead, shrouds it in shame, forcing it to assert itself through unexamined, haphazard, or violent means.

As far as examining the result of our efforts to repress conflict, we don’t need to look much further than what’s happening in many leftist, “woke” spaces. Conflict has become so demonized and unacceptable that anyone who dares ask a question or bring up a differing opinion is at risk of being labeled an “abuser.” We’ve become so averse to offense, hurt feelings, and getting triggered, that we’ve attempted to shove any and all forms of conflict into the closet. However, this hasn’t eliminated the conflict, it’s only left it ripe for expression in the form of authoritarian control over “free speech”, smear campaigns, and widespread cultural division.

In order for any culture or society to survive and thrive, some degree of conformity and structure is required. Rules need to be followed, and values need to be upheld. Opportunities for veering off course need to be avoided, and systems need to be enforced in order to prevent society from descending into total chaos. (Yep. There’s that word again).

Whether we’re talking about bands of prehistoric hunter-gatherers or the twenty-first century societies we find ourselves in today, maintaining order has always been crucial to the survival of the group. That said, the intention for maintaining order and the ways in which conflict is dealt with has changed significantly over the course of human evolution.

Humans evolved from egalitarian societies in which individuals were highly interdependent. Social control was everyone’s priority and was reinforced by democratic means.

Largely as a result of the agricultural revolution, humans now live in hierarchical societies, where there is an unequal distribution of wealth, power, and resources. While conformity used to be necessary for the livelihood of each member of the group, now it’s promoted and enforced to protect those with the most power, wealth, and resources. For governments, organized religions, economies, political parties, workplaces, schools, and other hierarchical institutions that organize society as we know it, the predominant desire to maintain order comes from and benefits those at the top of the hierarchy.

Not only has the impetus for maintaining order shifted over time, but so too have our attitudes and approaches to conflict.

Hunter-gatherer societies had a variety of customs and practices to deal with and diffuse conflict in constructive, honest, and democratic ways. Whether through humor, public airing and debate, mobility in switching to a different band/group, or otherwise, conflict is seen as a normal and expected part of life.

Typically, [hunter-gatherer] residences are all located within close proximity [to one another]. Therefore, any loss of control or display of anger is immediately noticed by fellow residents. This type of arrangement allows for all of the members of the group to witness, and participate in, conflicts that may arise within the camps. The huts of approximately forty or so people are ordered in a circular arrangement, and this allows the subtlest acts of antisocial behavior to be witnessed promptly. When an individual of the group feels slighted, he or she will talk about it so that others will hear the complaint. This behavior allows the grievance to be publicized which reduces the burden of frustration on the individual. Clearly, this lack of privacy acts to moderate conflicts by defusing them before they become too serious. - William Lomus, Conflict, Violence and Conflict Resolution in Hunting and Gathering Societies

Instead of acknowledging conflict and working toward solutions in a mutually constructive manner, it seems that modern culture has sought to deny it’s existence entirely.

From the demonization and repression of sexuality to the fear and avoidance of conflict, anything that’s at risk of threatening hierarchical power and control is implicitly and explicitly prohibited throughout society.

The story of Ares & Aphrodite is ripe with multiple conflicts related to sex and relationships specifically, so it doesn’t surprise me that so many modern day interpretations of this story claim that it represents something harmful, damaging to oneself, one’s relationships, and to society as a whole.

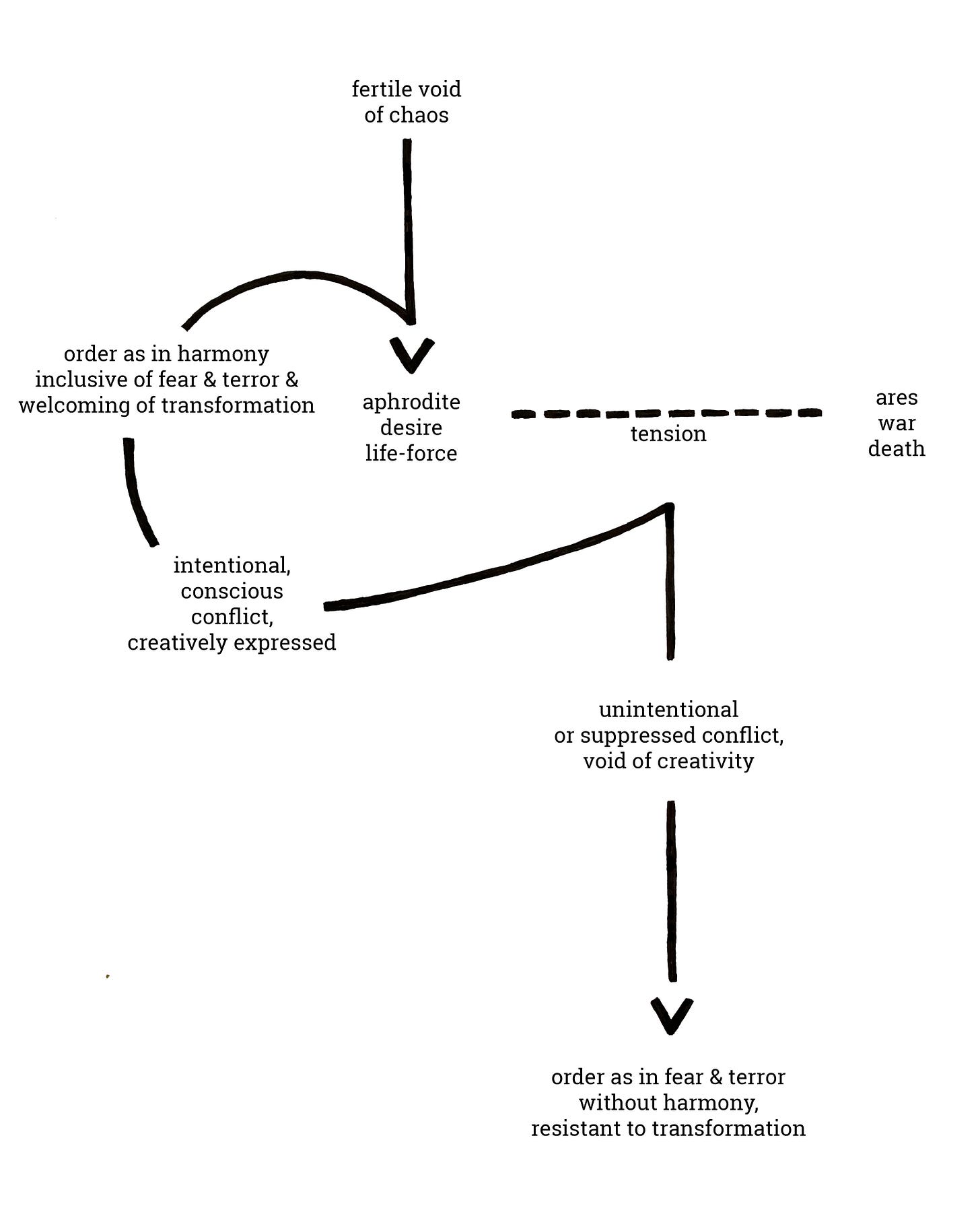

Let’s for a moment discuss the difference between “tension” and “conflict”. Similar to order and chaos, tension and conflict exist on a shared spectrum. Conflict won’t arise without some degree of tension, and without conflict, the tension may never be realized. Perhaps then, we can look at conflict as the realized, tangible expression of tension.

When considering the story of Ares & Aphrodite, and in examining the ways conflict emerges in modern society, it seems that tension is unavoidable and ubiquitous (maybe even enticing), and yet the way that tension is realized can vary, depending on how conscious and honest we are about the existence of this tension to begin with.

Returning to the earlier example, there seems to be an acute tension between our desire to make the world more inclusive and equitable, and the means by which we believe doing so is possible. Such a monumental degree of creativity (equality for all) will undoubtedly require an immense amount of conflict in order to come to fruition. At the very least, heated debates, a resurfacing and processing of trauma, and a reexamination of hierarchy, patriarchy, capitalism and the structures and systems they’ve produced over hundreds of years will all be necessary parts of the process.

What could prove to be constructive, creative, and inspiring has instead become regressive, stagnant, and unproductive, provoking rifts and chasms even between groups of people that ultimately have the same goals.

The tension represented by Aphrodite’s “too much”-ness in addition to the tension inherent in her connection to Ares can manifest itself in two ways. It can be controlled, denied, and kept secret; entangled in a net of shame and finger wagging, and choked by Jordan Peterson and Hephaestus’ version of “order.” Or, alternatively, it can prove fertile – giving birth to the messiness of life itself, generating a version of order that’s inherently creative, like threads on a loom waiting to be transformed into art.

If we allow it, conflict can be a gift, as it invites us to examine something that’s begging to be realized. Conflict is only a threat when we deny it’s presence and it’s fertile, creative, and transformative power.

"Confusing being mortal with being threatened can occur in any realm. The fact that something could go wrong does not mean that we are in danger. It means we are alive. Mortality is the sign of life." - Sarah Schulman, Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm

Aphrodite was a force, and needed an appropriate match. The lack of constructive tension in her relationship with Hephaestus is what propelled her toward Ares. Their union represented the undercurrent of what all sexual polarity, fertility, and creativity is built on – they were positive and negative charges, the masculine and the feminine, night and day, birth and death.

Aphrodite introduced desire and life-force, Ares brought action, will, and the transformative power of death. Together, they created life in the form of fear, terror, and harmony – the ingredients that drive us toward and away from love; A recipe for feeding the tension that propels us forward, away from stagnancy and toward creation.

The root of “tension” is the Latin tensionem, meaning “a stretching”. The presence of tension, and the conflict it may produce, asks us to expand, to grow, and to realize our potential.

Society, inherently fearful of death and the disruption of hierarchical power, and bent on maintaining the status quo, may pressure us into feeling ashamed about our desire to grow beyond where we are now. Judgmental parents or jealous friends may also try to foil this process of (re)birth, as it represents a version of power and creativity that can prove threatening. However, we need to remember that bronze nets are no match for the driving force of transformation.

In returning to our story, one of the more minor characters seems to play a rather significant role – Helios, the Sun God, who exposes Ares and Aphrodite’s affair. There is something to be said for the power of daylight in exposing that which would rather exist in the dark and remain in the underworld of our subconscious. Secrets and the tension they conceal will never stay hidden forever, and it’s up to us to decide how we’d like to invite these underworld demons into the light of day. We can be honest with ourselves, and invite them out intentionally, or, we can wait for them to grow in strength and ferocity, but at that point, we won’t have control over how they may choose to express themselves.

Desire is implicit to the human experience in that desire is responsible for bringing us everything from love and sex, to art, and to progress as a whole. In order for our desires to express themselves, there needs to be some degree of tension between what we have and what we want; where we are and where we’re going; who we are and who we’re becoming.

“We can’t just stop. We’re not rocks—progress, migration, motion is… modernity. It’s animate, it’s what living things do. We desire. Even if all we desire is stillness, it’s still desire for.” - Tony Kushner, Angels in America

When we deny our desires, or fail to engage with them honestly and constructively, we are individually and collectively at risk of alchemizing tension into something destructive, as is evidenced by none other than civilization and its discontents.

Desire and the tension it invokes can feel threatening, unnerving, and overwhelming. Fertility and creativity contain death, after all, and our desire to create something new is deeply subversive. It’s therefore not surprising that as a culture we’ve become so terrified of the power contained within desire, nor is it surprising that we’ve become so fearful of female sexual power; a power that Aphrodite undoubtedly represented.

Before the war on drugs, the war on terror, or the war on cancer, there was the war on female sexual desire. It’s a war that has been raging far longer than any other, and its victims number well into the billions by now. Like the others, it’s a war that can never be won, as the declared enemy is a force of nature. We may as well declare war on the cycles of the moon. - Christopher Ryan, Sex at Dawn

Desire and tension can manifest intentionally and constructively, inclusive of the terror, fear and harmony inherent to all creative endeavors. Or, in seeking to suppress desire and tension, we are left with a version of “order” that is void of harmony and informed only by terror and fear. One is progressive, and cyclical, the other is suppressive, and inactive.

We live in a world in desperate need of widespread change. At times, we may also feel that our own personal world is in desperate need of this sort of change. Hopefully, in revisiting this ancient story, we can feel comforted by the primordial nature of the process of transformation, and the significance of what it represents.

The story of Ares and Aphrodite is a story about the power of cycles and their capacity to bring forth new growth. It is a story that reminds us about the birth and death inherent to all fertility and transformation. When we repress the importance of desire and tension (and the creativity that emanates from both), we become severed from our own vitality, incapable of participating in the essential, cyclical nature of life itself.

In order to honor transformation in our own lives, we need to trust that our desires are worthy of being greeted by the light of day. By doing so, we are given an opportunity to turn a row of threads on a loom into art, well aware that whatever we create may eventually be destroyed by our future desires, once again arriving unannounced from deep within the fertile void of chaos.

Astrological context & inspiration:

For the past month, Mars and Venus have been conjoined in the sky in the sign of Capricorn, following Venus’ retrograde in the same sign. The length of their conjunction has been unique, as their encounters are normally far shorter. On March 11, they will begin to separate.

How have the themes of Ares and Aphrodite appeared for you over the last month or two? How have you come into contact with your own desire and the tension it illuminates, and/or how have you been affected by someone else’s desire?

If you want to learn more about how these themes exist within your own natal chart, and you enjoy the process of interpreting and relating to mythological stories, join my April Lunar Circle. It’s a month-long workshop teaching you how to see yourself, other people and the planet through the lens of astrology and archetypal psychology.

So poignant, at a time when our collective shadows are actively being projected onto an “enemy” so we can fight our battles against the other - instead of lighting up the shadows within and using the tension to create a love affair with our own chaos. Thank you for weaving this gift to share with us!

I really love this ! So many layers in this article !!

I also love the timing. For all astro nerds out there, the wild tango between Venus and Mars through the last quarter of the zodiac has been written about extensively. You’re taking it to the next level by going DEEP.

Venus/Aphrodite is indomitable, same for Ares… Of all the Olympians, these two archetypes are well known to be unpredictable and rebellious. They just follow their strong desires and the rest of the gods can just try to follow the pace or pick up the pieces.

The one thing that fascinates me is that Aphrodite/Venus is older than Zeus/Jupiter himself. She was born from a “piece” of Ouranos, the grandfather of Zeus. Her primordial energy was there before the reign of the king of the gods on Mount Olympus. She was there before the “new order”, before civilization, before war, before the building of the first temple…

She loves love as Mars loves war, just for the sake of it. They’re both RAW forces that contribute to the exuberance of Life itself. They don’t need big plans, they just live in the moment.

Of course, the rest of the Gods want to put a “ lid on the saucepan”, they need stability. Same for patriarchy of course… The times change but the same control freaks are still afraid of female sexuality. This fucked-up culture that we live in doesn’t belive in Heaven of Hell anymore BUT she’s still frightened of the impetuousness of the divine feminine.

Such a nonsense, because at the end of the day, it’s like being afraid of Life itself.

(Or choosing only the preservation aspect of Life versus the exploration/expansion part of it)

I guess that, as a conscious species, we’re still evolving…